Generally speaking, one should only consume processed foods prepared under the supervision of a rabbi or an accepted kashrut supervision agency.

Special symbols (called hechsherim; singular: hechsher) unique to each agency appear on the labels of food products. There are hundreds of such markings, some national, some local, some trusted by nearly all kosher consumers and others not.

Consumers encountering unfamiliar hechsher symbols should check with a rabbi for advice as to the reliability of the symbol in question.

Many of these symbols and the names and addresses of the agencies and institutions that use them are listed conveniently on this website maintained by Arlene J. Mathes-Scharf.

The Letter K on a Label

Some products are marked with just the letter K by itself.

Unlike the hechsher marks of supervising agencies, which are copyrighted and so may be used only with permission, the letter K (which cannot be copyrighted) generally indicates only the manufacturer’s own assertion of the kashrut of the product.

Sometimes, however, the K is used on a product that actually has been produced under rabbinic supervision, but which is sold without the hechsher because of a corporate policy.

Manufacturers will usually respond with the name of their supervising wrabbi or organization if asked, but consumers should check with a rabbi for advice about the use of products marked with only a K.

The question of the use of the letter K as a kashrut symbol is discussed by Rabbi Kassel Abelson in a responsum approved by the Committee of Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) in 1993.

Why do we need a Hechsher?

There are a number of good reasons why kosher foods require formal rabbinic supervision during production. These include many foods that might not, at first glance, seem to need it.

One reason has to do with the equipment in which the product was prepared.

Often, the same cauldrons, pots, and baking equipment are used for producing something non-kosher (such as pork and beans) and then used for another product that might appear to be kosher (such as vegetarian beans).

When the product is marked with a hechsher, however, the consumer can be certain that the ingredients and the equipment have been inspected and that the product is fully certifiable as kosher.

Merely perusing a list of ingredients can never provide the same level of certainty.

A second reason for needing a hechsher has to do with governmental food and drug labeling laws.

The laws and standards of government entities are based on civil laws guided by many different concerns, but not by Jewish law. A product reasonably considered non-dairy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, as noted, may in fact be considered dairy by the standards of normative kashrut observance.

A reference to “natural flavor” may sound innocuous, but the product may still be made from animal sources. The willingness to go beyond the information on the label is a key part of keeping kosher.

In addition to their standard hechsher symbol, many kashrut supervision agencies affix the letter D or the word “Dairy” to make explicit the non-pareve status of the product.

The letter P usually designates “Passover”; agencies typically add “pareve” after their hechsher when appropriate.

Occasionally “Meat” or “Fish” will appear after the hechsher as well.

In the latter case, as on products such as Worcestershire sauce, this is because there has been a custom not to eat fish with meat, as noted, even though fish is considered pareve.

However, since we do not enforce this custom, based as it is on the supposition that there was some physical danger inherent in eating fish and meat together, there is no reason not to use a substance that contains fish products, like Worcestershire sauce, together with meat.

DAIRY EQUIPMENT (DE)

Some products marked as pareve might carry an additional designation such as “DE” or (less commonly) “ME.”

This indicates that the product itself is pareve, but was made on either dairy or meat equipment that had been cleaned, but not restored to a pristine (non-meat, non-dairy) state through halakhic procedures.

Products with these designations are considered pareve and may be served after any meal on either pareve plates or on dishes appropriate for the meal being served.

There is a caveat regarding DE products, however: although they may be served at a meat meal, they should not be served at the same time as meat itself (Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 95:2).

Similarly, ME products should not be served at the same time as dairy products. For example, chocolate chip cookies marked as DE may be served after a meat meal, but not together with the meat itself.

To understand the rationale behind this concept, it is necessary to understand the distinction the halakhah draws between products considered able to impart flavor directly from the flavor’s source (called notein ta·am) and those in which the flavor imparted is deemed to come from a flavored item, not from the original source of the flavor (notein ta·am bar notein ta·am).

Foods cooked in a pot, for example, are deemed to leave a taste of some sort in the pot, and the halakhah holds that this taste can be passed along to the next item cooked in the pot. A third generation of taste no longer needs to be taken into account, however.

Products marked DE can therefore be considered pareve because the level of dairy absorbable by the final product, if any, is in the category of notein ta·am bar notein ta·am.

Fruits and Vegetables and Hechshers

Natural unprocessed foods, such as fruits and vegetables, may be purchased without any formal kashrut designation. They should, however, be thoroughly washed before use. Items such as sugar and flour also do not require a hechsher.

A good rule of thumb is this: if a food product has been through cooking or extensive processing, it should not be used unless it has a hechsher.

As always, questions about which products require a hechsher or that can be used without a hechsher should be addressed to a rabbi.

Suffice it to say, the changes in food manufacturing processes and in labeling laws have brought about two major results: a growing number of kashrut supervising agencies and an inability to rely simply on a casual perusal of a product’s label.

Fortunately, the amount and variety of foods produced under rabbinic supervision continue to grow.

Adapted with permission from The Observant Life.

Authors

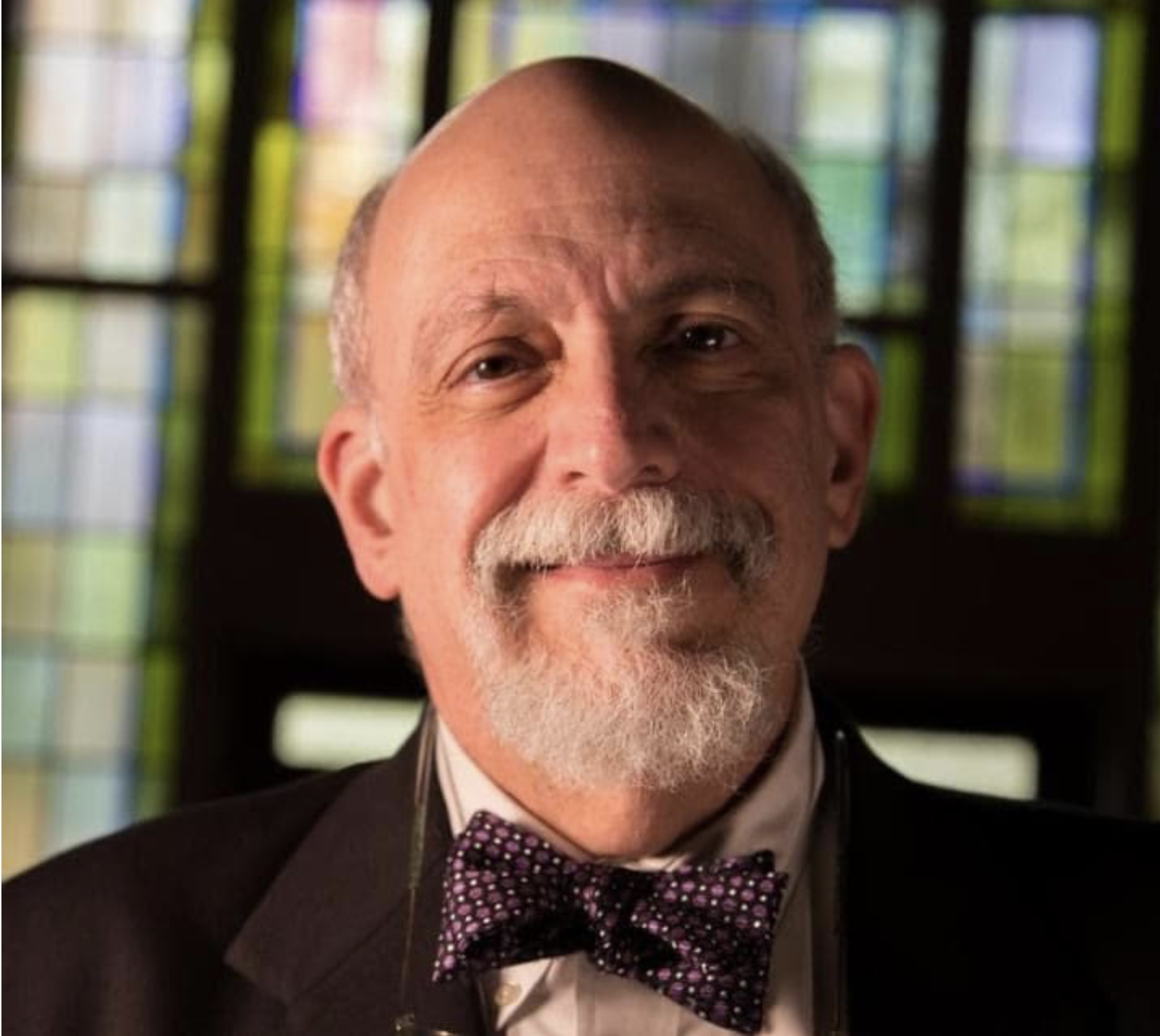

-

Rabbi Paul S. Drazen (1951-2018) spent two-thirds of his rabbinic career serving individual congregations and one-third on the staff of USCJ, all the while creating programs and educational opportunities to make Jewish observance and practice clear, accessible, and attainable for everyone.

View all posts -

The Observant Life: The Wisdom of Conservative Judaism for Contemporary Jews distills a century of thoughtful inquiry into the most profound of all Jewish questions: how to suffuse life with timeless values, how to remain loyal to the covenant that binds the Jewish people and the God of Israel, and how to embrace the law while retaining an abiding sense of fidelity to one’s own moral path in life. Written in a multiplicity of voices inspired by a common vision, the authors of The Observant Life explain what it means in the ultimate sense to live a Jewish life, and to live it honestly, morally, and purposefully. The work is a comprehensive guide to life in the 21st Century. Chapters on Jewish rituals including prayer, holiday, life cycle events and Jewish ethics such as citizenship, slander, taxes, wills, the courts, the work place and so much more.

View all posts